How federal pullback reshaped the Macon Housing Authority

The agency, created more than 85 years ago, has adjusted as the federal dollars directed toward public housing have waned.

This story is part of “Power,” a series by The Melody examining local authorities — quasi-governmental bodies that make consequential decisions about housing, water, transit, development, health care and public spending — that shape life in Macon-Bibb County.

When the Macon Housing Authority was created more than 85 years ago, the newspaper described its goal as “Macon’s initial attempt to clear her slums.”

More than 160 homes were demolished. Nearly $2 million from the federal government helped the authority build the city’s first two, low-rent public housing developments: Tindall Heights and Oglethorpe Homes.

Tindall Heights was for Black residents and Oglethorpe was for white people, in accordance with segregation Federal Housing Administration policies of the time.

When the red-brick buildings at Oglethorpe and Tindall were finished in 1940, a year before America entered World War II, a newspaper cost 5 cents. A pint of peach ice cream from Dixie Dairies cost 15 cents. A Sunday dinner special at a downtown restaurant cost 35 cents.

The more than 500 apartments were snatched up quickly by tenants. A family of four paid about $13 per month for rent and utilities.

But, over the decades, the federal dollars directed toward public housing has waned, and the authority has been forced to adapt.

Today, instead of the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration’s approach to housing as a fundamental right, housing authorities in Macon and elsewhere operate much like for-profit developers, searching for efficiencies and making development deals that hinge on private money.

In 2003, when the 188-unit Oglethorpe Homes, near Mercer University in the Beall’s Hill neighborhood, was razed, a new kind of development took its place.

Tattnall Place is a 97-unit mixed-income development made up of townhouses and duplexes between Calhoun, Hazel, Shamrock and Oglethorpe streets. Tenants living there include 67 who are low-income and pay a reduced rent through the Section 8 program and 30 tenants who pay the market rate for rent.

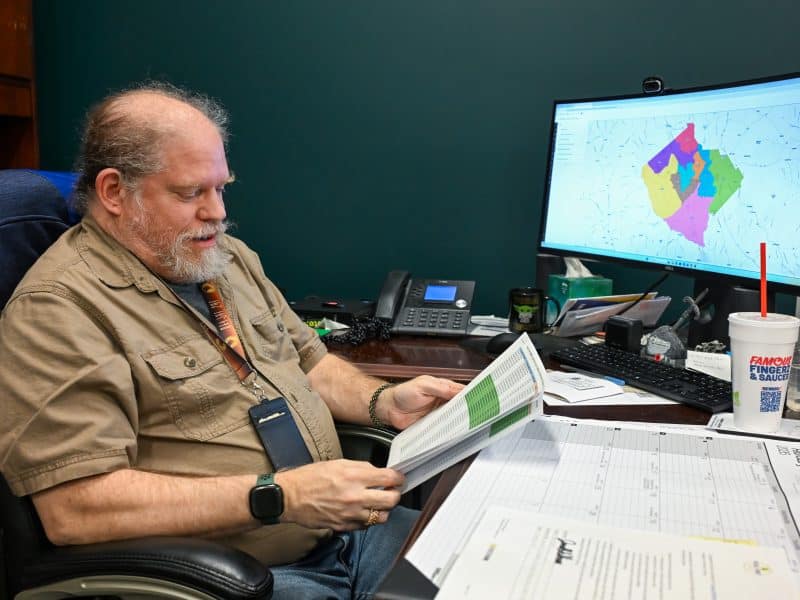

“You can’t point at one door and say, ‘Oh, that must be Section 8’ or ‘Oh, that must be a tax credit (unit) or a Mercer student,’” Macon Housing Authority CEO Mike Austin said.

The public doesn’t know, he said: “And that’s the beauty of it.”

Tindall Heights, a 142-unit public housing development where soul music legend Otis Redding grew up along what is now Little Richard Penniman Boulevard, was demolished in 2016. It was replaced by Tindall Fields, a four-phase, $45-million development featuring an apartment building, a seniors-only apartment building and multifamily homes. All told,133 of the 270 units are voucher-based or have a capped rent.

Like most of the housing authority’s work, the new Tindall and Tattnall developments were prodded along by the authority’s spin-off nonprofit entities, which are allowed to entice developers with tax credits and special financing terms the housing authority itself can’t use.

A web of nonprofits

The Macon Housing Authority board meets on the second Thursday of each month at 4 p.m. in the board room at 2015 Felton Ave.

Upon adjournment, it is almost always the case that another meeting — held by one of its many subsidiaries — is called to order. Authority members stay seated because they also sit on the boards of these subsidiaries. It makes for a mind-bogglingly complex organizational chart.

The Macon Housing Authority began creating nonprofit subsidiaries in the late 1990s as a way to finance, develop, own and manage each of its residential properties. The authority’s reliance on private money to build affordable housing occurred gradually over decades of political, economic and societal shifts.

The authority’s nonprofits not only help limit liability to the authority but also allow it to indirectly form partnerships with corporations — including monied private institutions like banks and insurance companies.

Some of the nonprofit entities include In-Fill Housing Inc., In-Fill Housing II Inc., Consolidated In-Fill Housing Inc., McAfee Towers Inc., Bowden-Pendleton Inc., Central City Apartments LP, Anthony Homes Inc., Central Georgia Affordable Housing Management Fund, Grove Park Village Inc., Blackshear Village Inc., Northside In-Fill Inc., Mounts Homes LP, Davis Village LP, Pearl Stephens Management Services LLC, Peake Point LP, MA Merger Corporation Inc. — among many others.

These affiliated nonprofits also are able to apply to the state for tax credits to build or rehabilitate affordable housing.

Tax credits work like this: Companies financing affordable housing get a 9% or 4% break on annual taxes each year for 15 years if they put up money to help build affordable housing. The tax break can exceed the amount of money companies loan nonprofit developers, incentivizing companies to finance developments.

The creation of limited partnerships, incorporations and limited liability companies also allow the authority to invest in and develop affordable housing out-of-town and even out-of-state, a drastic change from the 10-mile radius of jurisdiction the authority had when it was formed in 1938.

A recent attempt by the authority to develop an affordable housing complex just outside of Charlotte, North Carolina, ended up falling through. Had it succeeded, it would have marked the authority’s first out-of-state development.

Public housing becomes affordable housing

When Austin started working for the housing authority in 1997, Macon had 2,300 units of public housing, which he defines as residential properties that are owned and operated by the housing authority.

“We’ve diminished our public housing stock significantly in favor of tax credits and Section 8,” Austin said in a recent interview. “Believe it or not, we only have 219 units of public housing.”

What happened to Macon’s stock of public housing is similar to what happened to those in cities across the country; squalor and concentrated poverty attracted crime.

“The landscape and political support of public housing just fell off the cliff,” Austin said.

Changing attitudes in Congress about funding for public housing ultimately resulted in fewer and fewer federal dollars being earmarked for housing authorities, which struggled to shoulder the costs of maintaining aging stocks of public housing.

In the 1970s, Section 8 vouchers started becoming popular and local housing authorities were charged with administering the program on behalf of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. The vouchers allow tenants to rent privately-owned dwellings they otherwise couldn’t afford.

Section 8 vouchers work like this: The voucher holder is responsible for finding a suitable place to rent from a landlord who accepts the voucher.

The tenant typically pays 30% of their “adjusted family income” toward rent and utilities. The local housing authority pays the difference between that and whatever amount the private landlord charges for rent.

The era of building new, large-scale, red-brick public housing developments came to a screeching halt when Congress passed the Faircloth Amendment, effectively ending new construction of new public housing developments in 1999.

Many public housing advocates had been pounding on HUD, “saying ‘Look, you owe us billions of dollars in backlog because what you’re giving us, it’s not keeping up.’ That’s been a political football forever,” Austin said regarding the dearth of federal money. “So, we got wise and said, ‘To heck with this. Let’s get out of the public housing business.’ Most people did that. Most housing authorities were just like, ‘no.’ ”

As federal support diminished, housing authorities across the country took the same path as Macon: They began looking to private money and private property owners to continue providing affordable housing.

Now, the Macon authority is working to convert its remaining stock of public housing into voucher-based properties or transfer them to a nonprofit subsidiary and improve them with tax credits.

The need for a new business model

The Macon Housing Authority’s financial margins are thin. Its income takes the form of fees collected from developers, HUD and bond issuance, as well as investments.

“We just try every year we look at the budgets, you know, we only get what we have to get,” Austin said, noting that the authority’s offices are far from lavish.

Unlike private developers of low-income housing, the authority is obligated to reinvest its profits back into building and maintaining affordable housing.

When it comes to federal funding, “it’s never enough,” Austin said.

In recent years, he said the authority has had to cut back on how much it contributes to health insurance for its roughly 105 employees.

“We try to be cutting-edge. … so that we can do a lot with a little,” Austin said. “In every area, we try to be lean.”

The future of federal housing assistance is uncertain, especially as President Donald Trump plans to gut it. Austin said another overhaul might be due.

“I’m looking at Trump’s ideas and he’s like, ‘Well, let’s give all the housing to the states. This is new.’ And I’m like, ‘No, it’s not. Clinton-Gore came up with that years ago.’ That’s not nothing new. It’s not necessarily a bad idea, It just never really took hold.”

Asked how the housing authority stays afloat with thin margins for income and expenses, Austin said, “We’re not going to stay afloat if we don’t adopt a new business model.”

The Macon Housing Authority board meets on the second Thursday of each month at 4 p.m. in the board room at 2015 Felton Ave. Current board members include: Melinda D. Robinson-Moffett, Eric P. Manson, Jeff C. Battcher, David A. Danzie Jr., JoAnn Fowler and Ethiel Garlington. The Melody has compiled meeting minutes and board documents, including bylaws, which may be viewed here.

Before you go...

Thanks for reading The Macon Melody. We hope this article added to your day.

We are a nonprofit, local newsroom that connects you to the whole story of Macon-Bibb County. We live, work and play here. Our reporting illuminates and celebrates the people and events that make Middle Georgia unique.

If you appreciate what we do, please join the readers like you who help make our solution-focused journalism possible. Thank you