Stratford tennis legend Jaime Kaplan back in swing after cancer fight

From Wimbledon trips to eating spicy food, the Macon sports icon feels like herself again.

Former tennis star and Stratford grad Jaime Kaplan doesn’t have her dark hair back.

That ship sailed for good in 2010 when she faced extramedullary acute myeloid leukemia.

But here in her 21st month since being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer — after overcoming leukemia in 2010 and then handling amyloidosis in 2020 — she’s pretty much herself.

Including her silly. She’s got that back.

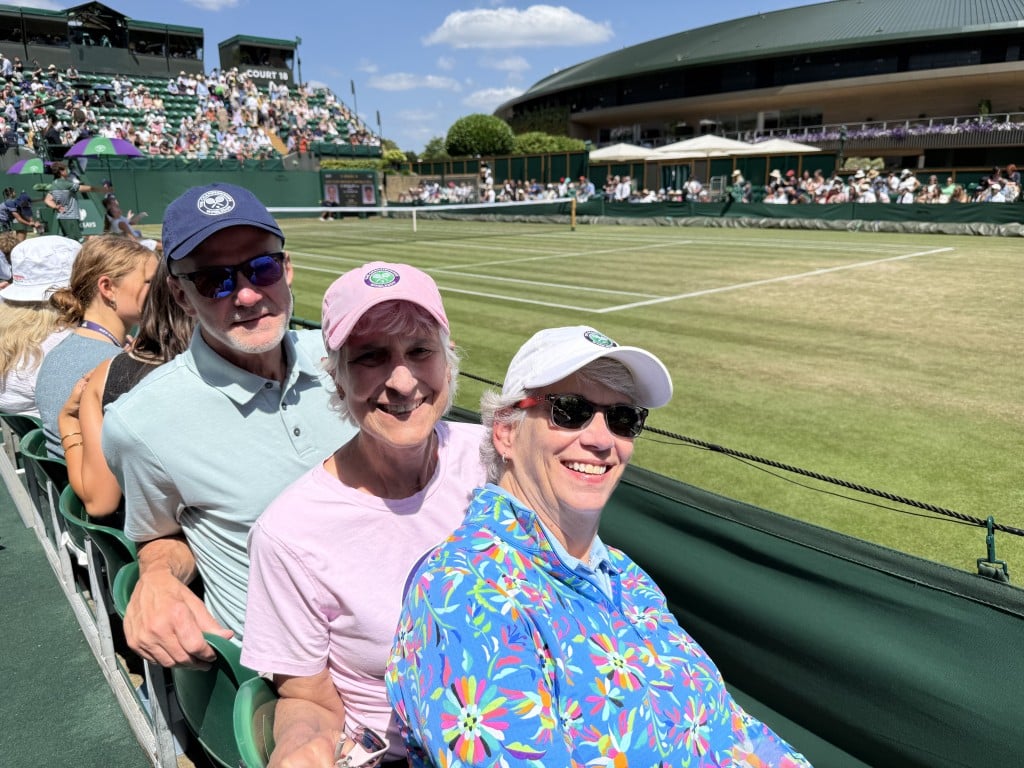

Sitting on her porch a few months ago, before she and buddies Patty Gibbs and Jeff Battcher started on their Wimbledon 2025 Tour for a week, Kaplan was talking about the last several months.

The period included a stretch where her hands and feet were something of a mess as she battled neuropathy — a nerves-related condition that can cause weakness, numbness and pain in the hands and feet — off and on for several months.

Sitting on the table aimed at her was a camera. She is asked about different issues of the past 21 months, including her feet.

All of a sudden, a goofy grin crossed her face, and she stuck her feet in front of the camera and wiggled them.

“See my feet?” she said with a giggle. “You can edit that out, right?”

Kaplan has packed a lifetime of memories — good and bad, chilled and stressful, worried and optimistic — into the last two years. She went through it all: wondering what was wrong, worrying about how much time she had left, exhaustion and losing weight, traveling abroad, recovering and even visiting Wimbledon for the first time in 20 years.

She can dabble in spicy foods again — not pig out, but dabble.

“I asked the doctor when I was at Emory, ‘The fact that I can’t have spicy food, is that because it’s going to hurt me or because of the aftermath?’” Kaplan said. “‘The aftermath.’ And I’m like, ‘Well, I’m experiencing that anyway.’ So I occasionally I have a teeny bit of spicy.”

That’s just one example of the progress and changes Kaplan has undergone since being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in December 2023.

Kaplan has been as close to normal as normal can be, and maybe a little better, for most of about 15 months. She couldn’t do dishes or take a normal shower, among other normal routine tasks, for months. She would sometimes sleep for half a day and underwent assorted digestion adjustments, had hand and feet issues, and couldn’t do much of anything for most of the first several months of treatment.

Now, there’s not much of anything she can’t do that she wasn’t doing before the diagnosis — from golf to travel to work.

Returning to normal

Kaplan retired from pro tennis in 1989 but remained active on the court for a while afterward. She went from athlete to coach, teacher, fundraiser on a variety of levels, consultant, life and guidance counselor, and adviser, booster and ambassador of tennis, Macon and sports — among other things.

But she’s back in action, almost to her pre-diagnosis level. She said in December that, outside of some hitting with Stratford players on occasion, she hadn’t much picked up a racquet since 2012.

Now she’s regularly playing “red ball,” a fairly new sport that’s not far removed from pickleball — other than a bigger ball and bigger racquets. It’s a little closer to tennis.

And while she can’t happily dive into bowls of chips and salsa, she can have some pepperoni on pizza.

“I’m doing better with pepperoni,” she said. “I can tolerate it.”

The reality is that almost nobody who gets cancer is ever cancer-free. Victims who ring the bell upon leaving a cancer treatment facility are in reality ringing a bell that indicates a cancer — and the variety of cancers is vast — is no longer dominant.

Back in December, Kaplan talked tentatively on the topic, a tentativeness shared by one or two of her doctors. Early in the month during regular scans, one doctor said she was in remission.

A month later came another visit to Emory.

“They’re like, ‘You’re stable, we don’t use that word with pancreatic cancer,’” Kaplan said. “The reason they don’t is because you never really get rid of it. You go into remission, then you’re in remission, remission, remission. And they say after five years, you’re cured.”

Kaplan has only a year checked off on that timeframe. She still has a cancerous growth on her pancreas. Even if she hits that five-year period, a reason cancer is rarely actually “cured” is because microscopic cancer cells can remain. They may have broken away from the primary location and are “undetected,” making regular monitoring a must.

There is a difference between “remission” and “cancer-free,” the latter being the very rare case where there is no detectable sign of cancer or cancer cells. You needn’t monitor something that no longer exists. Thus, there is always a chance of some level of recurrence and a need for permanent monitoring and checkups, Kaplan said.

Pancreatic cancer is particularly difficult because it progresses quickly, and there’s no solid method of early detection. It is a key component in blood flow and digestion.

“[It’s] the most complex collection of body organs,” said Kaplan, starting to grin. “Literally, all the [expletive] flows through your pancreas.”

Yes, there’s a little more potty humor to Kaplan these days, too.

Most anybody who has known Kaplan for years saw her 112-pound frame — that’s thanks to the digestion issues — when she was back to wearing a mask long after the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. She couldn’t hug anybody and for months couldn’t attend many events.

Back in April 2024, she was the guest of honor at a surprise celebration honoring her 500th win as a high school tennis coach. That sunny spring afternoon was likely the first time many in the invited audience of nearly 100 saw Kaplan since her diagnosis.

She looked like somebody who had gone through a cancer diagnosis, its related emotional rollercoaster and then the immediate chemotherapy: a little leaner, a little older — and tired.

Kaplan is happily heavier nowadays and has aged in years but not appearance — a marked change to the Kaplan of a year and a half ago.

A road to recovery

The only way to cover the last 21 months of Kaplan’s life is to cover life as it happens: In order.

Around the time of the yearly Five Star Kevin Brown/Russell Henley Celebrity Classic fundraising event in September 2023, Kaplan had assorted pains, especially in her back.

Kaplan tried to get scans for her back but was denied by insurance for a variety of reasons. She had a CT scan during her yearly amyloidosis checkup, though, and that would have to suffice.

The phone rang. The caller ID read “Georgia Cancer Specialist.”

She wondered why they were calling — probably for a donation, she guessed.

The caller didn’t have an ask, though.

On Dec. 5, 2023, after months of some physical issues, a tumor was discovered on her pancreas, and further testing indicated that it was a malignant tumor. It was intertwined with three blood vessels, rendering it all but inoperable under normal circumstances.

She began chemotherapy four days before Christmas. A bad reaction to the first session landed her in the hospital for a day.

The tumor was in such a high-traffic area that doctors said it was inoperable. She would lose her spleen, pancreas and celiac plexus, the abdomen’s nerve center.

“The doctor at Sloan-Kettering is the one that said there’s a double-digit chance that I wouldn’t make it out of the hospital, maybe not even off the table,” Kaplan said.

She recalled a story of a financially successful man who accepted all those risks, made it off the table and out of the hospital only to die three weeks later from a blurst blood vessel.

A few months and a few opinions later, there came a mild adjustment in the surgical possibility: it could be operated on, but there’d be little quality of and normalcy in life as a result.

As her chemotherapy neared an end, Kaplan — with more juice and energy — accepted a distinguished alumna award from Stratford and spoke at their commencement ceremony a few days later on May 18, 2024.

Few knew that the speech came a day after a round of chemo. She was ready to surrender her speech to her brother, Mike, but felt good enough to battle through the four-minute speech and did so with relative ease.

A visit that month to Vanderbilt opened the door to alternative surgical options as well as an adjustment in treatment. Another surgery was discussed and dismissed, and there was one test that showed the cancer had spread and yet another that said it hadn’t.

At the end of that month, her chemotherapy was over and considered a success. She made her first trip to a hair salon in many months.

Her cancer number remained monitored. It had been a scary 3,700 — 0-35 is normal — but was slowly dropping.

Kaplan went from the yearly June doctor visit in Boston regarding her amyloidosis treatment — she got that in 2020 — to a first meeting with doctors at Memorial Sloan Kettering in New York City to discuss MRI-guided, high-dosage radiation treatment. She returned a week later for an MRI-like “mapping” of her organs and the tumor.

There were five MRI-like treatments over the course of eight days. A body cuff, similar to ones used for blood pressure, was strapped around Kaplan’s midsection and inflated.

“And then when I thought they couldn’t inflate it anymore, they would inflate it some more,” she said.

Each such session lasted just short of two hours, and Kaplan had to remain completely still.

“[I] don’t feel a thing, but I’m about ready to crawl out of my skin,” she recalled. “That cuff being on me for so long and being still was pretty rough. By the end, the last probably 15 to 30 minutes, I could feel tears running down the sides of my eyes. It was tough.”

The stress of everything plus the difficult treatment put her down for a few days — although the impact wasn’t as exhausting as chemo.

Having a day between sessions allowed for some recovery and a little visiting of NYC. Of course, it came during a tennis major, which cut down on tourism.

“Getting ready to watch Wimbledon,” she posted on Facebook on July 14, 2024, in between sessions at Sloan Kettering.

Also watching was her friend — and well-known Macon sports figure and philanthropist — Jeff Battcher, who had started talking to Kaplan about going to Wimbledon for the first time.

Battcher asked Kaplan to go with him to Wimbledon’s 2025 iteration. She agreed, and it was filed away in the growing folder of wishful thinking.

“So every text message that we’ve texted in the last year has ended with ‘W 25!’” Kaplan said of Battcher’s encouragement campaign.

The next year and Wimbledon were nowhere on Kaplan’s radar as she waited out another round of treatment and its uncertainty.

So began a routine of scans locally or at Emory, six-month visits back to Sloan Kettering and a collection of assorted medication with accompanying side effects.

A few weeks after the sessions at Sloan Kettering in July 2024, she attended the U.S. Tennis Association’s Southern Summer Meeting in New Orleans. Scans a few weeks after that showed a slight shrinkage in her cancer.

She was pretty much back on schedule working for the Southern Tennis Foundation as well as again helping organize the latest Five Star Celebrity Classic, which last year raised $1.23 million.

That was a huge eight-day period for Kaplan.

As part of the Classic’s Monday-Tuesday schedule, she became the first woman added to Idle Hour Country Club’s Wall of Fame, joining the likes of Alfred Sams, Russell Henley and Peter Persons, among others.

That weekend was “Jaime’s Love Weekend,” a collection of events at John Drew Smith Tennis Center and Idle Hour intended to raise money for tennis scholarships in her name with the Southern Tennis Foundation. About $4,000 remains to reach the goal of $200,000, a much larger number than originally planned.

Officials from assorted tennis organizations as well as several former Kaplan players attended the weekend’s events.

After a few weeks to regroup came 11 days in Europe. Ever so slowly Kaplan gained weight and cracked a whole 120 pounds for the first time in a year.

The tennis freak hadn’t picked up a tennis racquet since about 2012. She soon changed that — to initially mixed results.

“I hit a couple of times with kids at Stratford,” she said. “I tried to hit with a couple of my boys. I think it was Samuel Barrow and Daniel Cohen. I tried to hit with them, and it felt so foreign. It felt like I had never played tennis before.”

All of a sudden, there was Kaplan, on a court and swinging. Granted, it wasn’t tennis — it was red ball, the child of tennis and pickleball, so to speak, with the same court as pickleball but using tennis-like racquets and a bigger ball.

She attended an introductory red ball session at Rhythm and Rally in the Macon Mall in November 2024, an event with plenty of familiar tennis faces. Before she knew it, she was on the court — with a racquet that felt familiar — and moving around.

“It’s just like playing tennis to me,” she said. “That was a happy day. Oh, it was awesome.”

The Kaplan of that evening was a familiar Kaplan — certainly not the same one of about seven months earlier, the worn down and worried iteration.

Then came December and the year anniversary of the diagnosis. It was quite the anniversary — that was when she was first told she was in remission. It made for an even nicer trip to New York City for the six-month checkup at Sloan Kettering.

By the time Christmas rolled around, Kaplan was more or less back to normal.

Across the pond

The change from July 2024 to July 2025 in Kaplan’s life and prognosis is staggering.

On July 14, 2024, Kaplan wanted simply to be in decent enough shape to watch Wimbledon from a room in New York City, completely unsure what the future held.

On July 5, 2025, Battcher, Kaplan and Gibbs hopped on a flight to London with a full schedule.

They saw “Phantom of the Opera” and “Les Miserables.” They ran into current Stratford player Lauren Little and former player Hadley Cullars. They toured the House of Commons and Westminster Abbey.

There were visits to pubs while bouncing around on buses.

And there was tennis at Wimbledon, some of which came in Martina Navratilova’s on-court box and on Centre Court in between visits with Gigi Fernandez, Pam Shriver, Kathy Rinaldi and Virginia Ruzici, among others.

One Kaplan mainstay picture shows her standing in front of the Wimbledon logo and a green facade back in 1985. In July, 40 years later, she took a picture in the same spot.

“It was like I was there for the first time,” said Kaplan, who last visited Wimbledon in 2005. “So many memories, a flashback, but certainly the most memories were 1985, the first time I played.”

The grounds of 2025 bore little resemblance to those of even 2005. Kaplan put Battcher and Gibbs in charge of getting the map of the complex and leading them to where they were supposed to go.

Kaplan was sitting in a fog of quasi-misery and hope in New York one year and sitting in Centre Court the next. What a life.

In August, she celebrated her other “birthday” — it had been 15 years since she got a bone marrow transplant to fix her leukemia. Earlier this week, she helped put on another Five Star Celebrity Classic.

The tentativeness of describing her situation as “in remission” is still there.

“In retrospect, I probably shouldn’t have put that word out there because I think a lot of people equate that with ‘cure,’” she said. “I still need prayers. Like I said, this stuff comes back 95% of the time, and it comes back with a vengeance.

“So, that’s why I said in my post that the little boogers are traveling around trying to reorganize. The tumor is still there. It sunk a little bit. It will never go away.”

Kaplan said it’s almost safe to say that the tumor itself is dead, but it was never alone.

“If it came back, that’s not where it would come from,” she said. “It would come from the fact that it’s in my blood, traveling around.”

Nevertheless, it no longer prevents Kaplan from traveling around or getting back to normal. In fact, she returned almost 100% of the time to coaching Stratford tennis last spring.

In the first season after the diagnosis, Kaplan only attended most home matches, wore a mask and moved slowly. A year later, in 2025, she was back to normal, with a co-head coach matchup.

“He does a lot of the things that I used to do,” she said of co-coach Sandy Burgess. “We talk. But Sandy’s brilliant about that stuff.

“When we get in the huddle, Sandy talks first to the team. He’s a great tennis coach.”

This year’s Five Star Classic marked two years since the initial back pain emerged and led to her diagnosis. The Classic of 2025 felt a lot like the Classic of 2022: normal.

“Last year I didn’t expect to feel as good as I did,” she said. “And then, this year, I didn’t expect to be here. This is a bonus year.”

Kaplan’s faith has allowed her to bypass concerns of mortality, of being on life’s clock, of whether there’s a recurrence. She’s just rocking and rolling.

“I’ve always just trusted God — from the second I got that phone call to come back down to Georgia Cancer,” Kaplan said. “It’s hard to describe. It’s this same thing I did when I had leukemia. I know this is different, but you know, I want to live like I’m living and not live like I’m dying. I do my thing.”

Before you go...

Thanks for reading The Macon Melody. We hope this article added to your day.

We are a nonprofit, local newsroom that connects you to the whole story of Macon-Bibb County. We live, work and play here. Our reporting illuminates and celebrates the people and events that make Middle Georgia unique.

If you appreciate what we do, please join the readers like you who help make our solution-focused journalism possible. Thank you